|

Has Housing Reached a New Tipping Point?

20/09/2017

barrysays

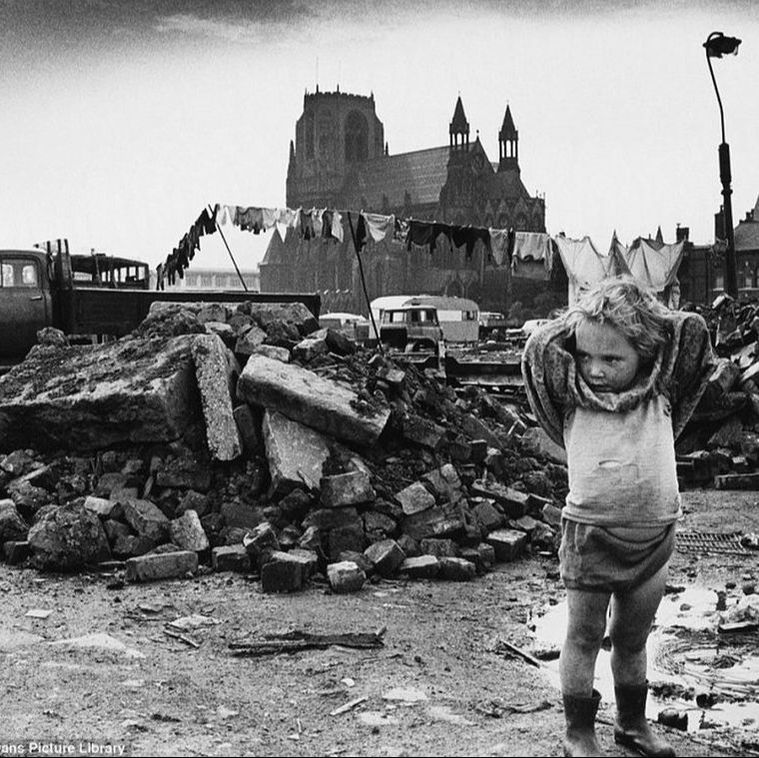

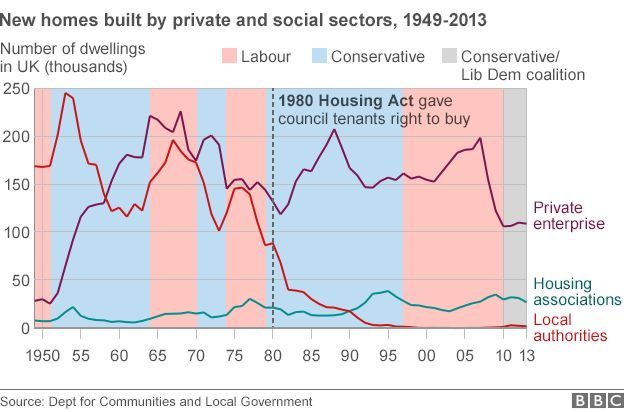

An insufficient supply of affordable housing seems to have become a common crisis worldwide. At this moment of massive human change, can new approaches to supply and demand bring new ways to solve an age-old problem?

Even those not familiar with Abraham Maslow and his 1943 paper "A Theory of Human Motivation" will still be able to inform us of their basic needs. Shelter is one of those basic human needs, along with breathing, eating and sleeping. And yet the developed world is undergoing a housing crisis once more, featuring homelessness, repossession and unaffordable costs to large sectors of societies that are struggling to come to terms with a sense of their own values. But are things about to change? A HISTORY LESSON

WHAT'S HAPPENING TODAY?

DOES EVERYONE NEED TO OWN A HOUSE?

SHOULD HOUSING BE ALLOWED TO BE A SPECULATIVE COMMODITY?

A TIPPING POINT

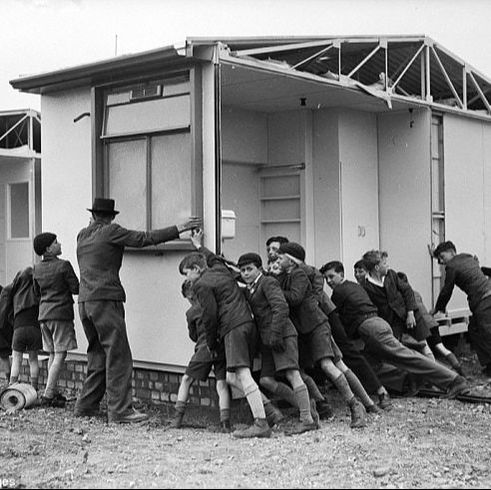

‘Prefab’ is a broad term that encompasses several different types of prefabricated building. Technically, any building that has sections of the structure built in a factory and then assembled on site can fall under the ‘prefab’ designation including both ‘modular’ and ‘panel’ built as well as fully ‘manufactured’ construction.

Barry Wilson is a Landscape Architect, urbanist and university lecturer. His practice, Barry Wilson Project Initiatives, has been tackling urbanisation issues in Hong Kong and China for over 20 years. (www.initiatives.com.hk).

2017/07/18

Superficial Beauty Conquering Urban Substance 2017/06/14 10 Simple Ways to Futureproof Our Cities 2017/05/11 Sponge Cities Absorb The Past 2017/04/11 Share And Share Alike |

The first successful construction of a fully modular home system did not materialize until 1933, with the Winslow Ames House by Robert W. McLaughlin and his company, American House, Inc. This innovative house was built with the help of a new exterior finishing material called Cemesto, a panel board made partly of sugarcane, patented by the John B. Pierce Foundation. The Winslow Ames House consisted of several room modules serviced by a service core to which all bathroom, kitchen, plumbing, and heating systems were attached. (image: CC-BY-SA 4.0)

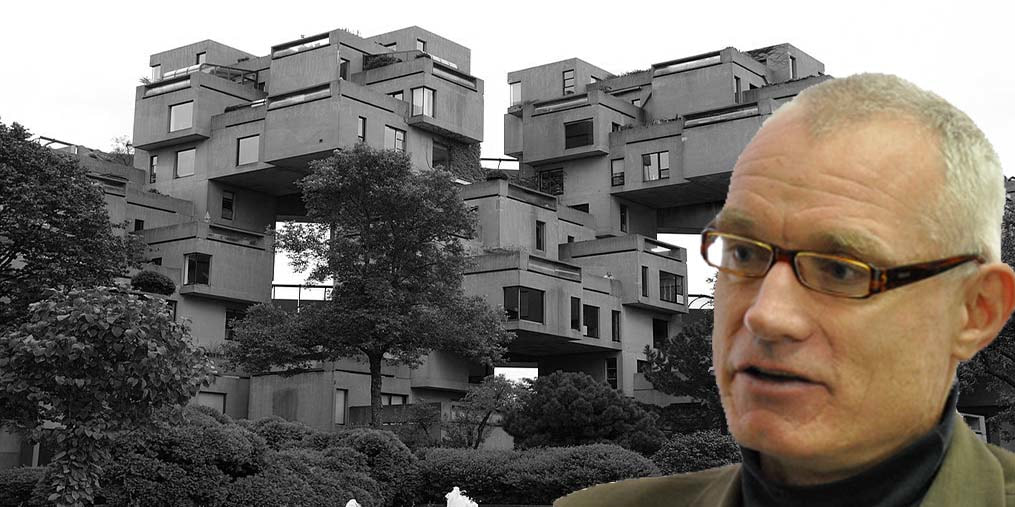

Container City II by Cmglee. New types of housing have arisen for those desperately looking for low rents: container houses and modular micro-apartments. Container housing, a creative reuse approach in which excess or discarded shipping containers are transformed into small homes, hit the mainstream consciousness in 2000, when the firm Urban Space Management completed the Container City I project in the Trinity Buoy Wharf area of London. (image: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

1972 Nagakin Capsule Tower, by Kisha Kurokawa consists of 140 self-contained prefabricated capsules, complete with bathrooms, cabinetry, and a built-in HiFi set. The tiny capsules, designed to be removable and replaceable, only measure 7.5 x 6.9 x 12 feet a predecessor to today increasingly popular micro-apartments. (image: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

|

Services |