|

Where Are All the Boomerangs?

20/01/2016

barrysays

I have just been ‘walkabout’ or should I call it ‘driveabout’ in Australia, my first trip to the country, traveling from Melbourne up through Sydney and ending in Brisbane. Before leaving we spent a lot of time reading stories about the country to our young daughters, filling their heads with iconic images of kangaroos, the opera house, boomerangs and didgeridoos. Not all of these were easy to find…

Taken in by the imagery of the boomerang sailing through empty blue skies, my eldest daughter pleaded to have one as a memento of the trip. Meeting this promise started to prove increasingly problematic as the journey wore on.

SEEKING CULTURAL HERITAGE ESSENTIAL IN A GLOBALISING WORLD

After driving over 2500km’s our experience of most of Australia was of generic strip development with big box sales outlets, shopping malls and car parks. Multinationals abound. The feeling rarely dissipated that we could have been in Los Angeles, Johannesburg or Basingstoke. Where was the real Australia?

As long ago as 1972, UNESCO adopted Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage at National Level.[1] It noted that cultural and natural heritage was increasingly threatened with destruction not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by changing social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage or destruction. Today there are 1031 World Heritage Sites 802 cultural, 197 natural and 32 mixed properties, in 163 countries.[2] Each of these sites is considered important to the international community. However these specific sites do not protect the overall character, traditions or identity of a region. The pace of change of those conditions identified in 1972 is now lightning fast, since the advent of the internet era. It is essential that development approaches for the planet focus on diversity rather than homogeny and differentiation above standardisation.

Back on the road, the genial owner of the surf shop in Grafton NSW, suggested that only the local indigenous Australians would have boomerangs, probably at a traditional arts and crafts outlet if I could find one. I tried. Tourist information in charming Kyogle provided me with telephone numbers of the local rangers who might be able to put me in touch with some local tribes. They didn’t answer.

Barry Wilson is a Landscape Architect, urbanist and university lecturer. His practice, Barry Wilson Project Initiatives, has been tackling urbanisation issues in Hong Kong and China for over 20 years. (www.initiatives.com.hk).

|

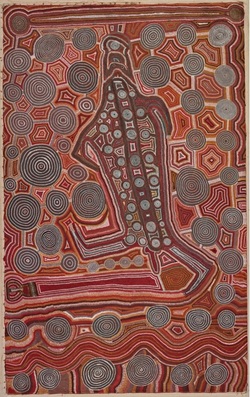

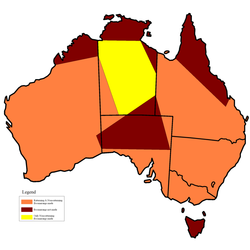

WHAT IS A BOOMERANG?

A boomerang is a thrown tool, typically constructed as a flat airfoil that is designed to spin about an axis perpendicular to the direction of its flight. Boomerangs have been historically used for hunting as well as a sport, ritual and entertainment. They are commonly thought of as an Australian icon.[5] A returning boomerang is designed to return to the thrower but was unknown to Aboriginal peoples in most of the Northern Territory, all of Tasmania, half of South Australia and the northern parts of Queensland and Western Australia.[6] Aboriginal peoples had no writing so could not record their words before the arrival of Europeans, who soon discovered that the returning boomerang was called a ‘birgan’ by Aborigines around Moreton Bay, and a ‘barragadan’ by those in north-western New South Wales. WALKABOUT

Walkabout historically refers to a rite of passage during which Indigenous male Australians would undergo a journey during adolescence, typically ages 10 to 16,[7] and live in the wilderness for a period as long as six months to make the spiritual and traditional transition into manhood.[8] Walkabout has come to be referred to as "temporal mobility" because its original name has been used as a derogatory term in Australian culture, demeaning its spiritual significance.[9] CULTURE FOR DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS (CDIS) OBJECTIVES

The CDIS establishes a common ground for culture and development actors to better integrate culture in development policies and strategies. CDIS methodology generates new data and builds capacities at the national level for: · Strengthening national statistic and information systems on culture and development; · Informing cultural policies for development; · Positioning culture in national and international development strategies and agendas; · Enriching the CDIS Global Database, the first international culture for development database. References:

|

Services |