|

Affordable Housing in Urban Centres Essential to Cities

30/9/2015

barrysays

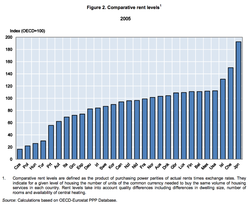

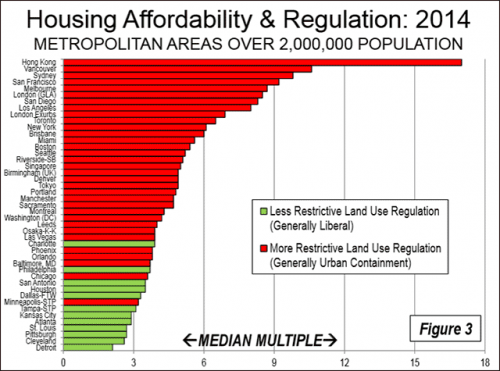

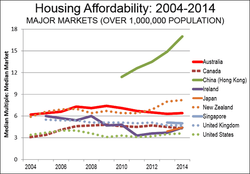

Last week I attended a Housing Forum hosted by the Urban Land Institute as a follow up to their Hong Kong Housing Workshop held in May this year. With real estate prices at record levels and purchase costs compared to peoples’ income making Hong Kong housing some of the most unaffordable in the world, both to buy or rent, it was no wonder the discussion focused on how to create more affordable housing for all income levels of the population. Housing affordability is an acute problem in many cities, not just Hong Kong and it is a multi-faceted issue that requires an integrated approach at many levels in order to adequately address the complexity.

2015/7/22

China Urbanisation Needs Rural Focus Not Just Mega-City Migration Related: Sustainable Approaches to Rural Development 2015/6/3 End of The Road for Stagnant Hong Kong? Related: SZ Overtakes HK in Economic Competitiveness 2015/5/12 Road Safety a Key Driver in Enhancing Urban Environments Related: Making our Road Transport Safer for Children 2015/4/21 Sowing the Seeds to Fuel the Future Related: China Finishes First Passenger Flight with Biofuel |

Affordable

housing is a term being ever more frequently banded around. But why is it so important and what are the implications for society? "In addition to the distress it causes families who cannot find a place to live, lack of affordable housing is considered by many urban planners to have negative effects on a community's overall health."[6] These workers are often forced to live in suburbia commuting up to two hours each way to work. Lack of affordable housing can make low-cost labour scarcer (as workers travel longer distances) (Pollard and Stanley 2007).

The price to income ratio is the basic affordability measure for housing in a given area. It is generally the ratio of median house prices to median familial disposable incomes, expressed as a percentage or as years of income. The ownership ratio is the proportion of households who own their homes as opposed to renting. It tends to rise steadily with incomes. References: [1] "Eurostat - Data Explorer - Distribution of population by tenure status, type of household and income group". Eurostat. 12 March 2015. [2] "Table 005 : Statistics on Domestic Households". Census and Statistics Department (Hong Kong). [3] Home sweet home is a rented property for many Germans. Julia Kollewe and Larry Elliott the Guardian. 16 March 2011 [4] The Housing Price to Income Ratio is the ratio of housing price (assumed to be a 100 square metre residential house) and household annual income, and is used as a measure of whether housing prices are at a reasonable level that household income can support. E-House China's data only covers new residential housing, and excludes the second-hand housing market. [5] Tilly, Chris (2 November 2005). "10". The Economic Environment of Housing: Income Inequality and Insecurity (PDF). Lowell, Massachusetts: Center for Industrial Competitiveness, University of Massachusetts. [6] Bhatta, Basudeb (15 April 2010). Analysis of Urban Growth and Sprawl from Remote Sensing Data. Advances in Geographic Information Science. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-642-05298-9. [7] Patricia Kirk. Making Mixed-Income Housing Work. Urban Land magazine. June 19, 2012 [8] Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. and author of "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” |

Services |