|

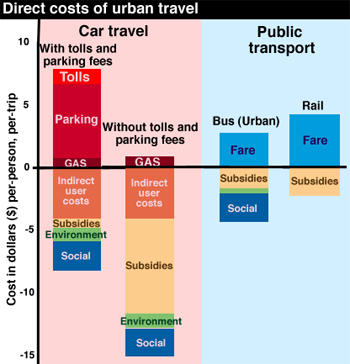

barrysays It’s been more than 20 years since I owned a car. Once you live in the centre of a big city, with good public transport alternatives, you just don’t need one. There’s never parking, plenty of congestion, you can’t drink alcohol, it’s expensive to run, can be stressful and it never seems to be quite the right size for each and every trip. Mostly though I have come to realise, just like cigarette smoking, it’s a selfish benefit enjoyed at the expense of others. The air and noise pollution produced, dedicated use of public space required and the safety risk posed to others, all run contrary to being a good urban citizen.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

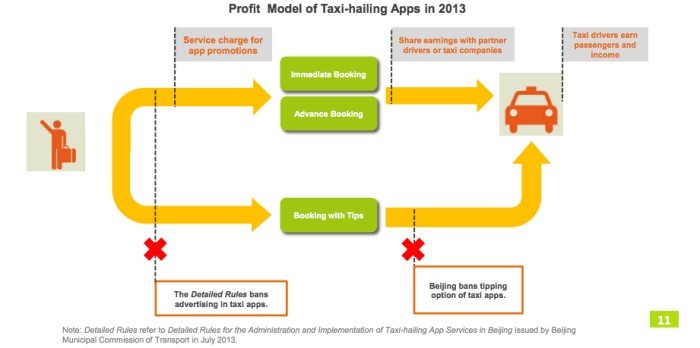

Uber is an American international company that developed the first mobile-app-based transportation network. The Uber app allows consumers to submit a trip request, which is routed to crowd-sourced taxi drivers. The service is currently available in 55 countries and more than 200 cities worldwide[1]. Since Uber's launch, several other companies have emulated its business model, a trend that has come to be referred to as "Uberification".[2]

People’s Uber is an app based service matching car owners with people looking for a ride.

CARPOOLING

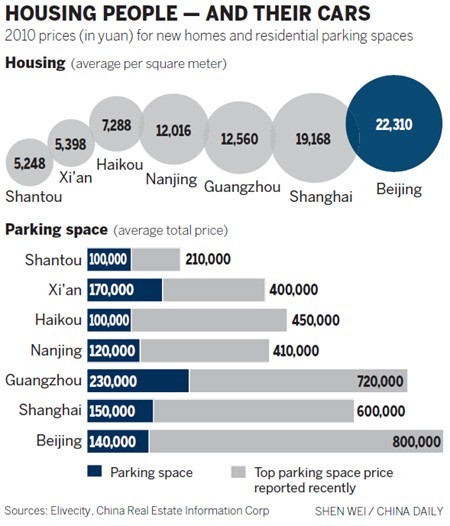

(car-sharing, ride-sharing, lift-sharing and covoiturage) The sharing of car journeys so that more than one person travels in a car. By having more people using one vehicle, carpooling reduces each person's travel costs such as fuel costs, tolls, and the stress of driving. Carpooling is seen as a more environmentally friendly and sustainable way to travel as sharing journeys reduces carbon emissions, traffic congestion on the roads, and the need for parking spaces. REAL-TIME RIDESHARING

(instant ridesharing, dynamic ridesharing, ad-hoc ridesharing, on-demand ridesharing, dynamic carpooling, all provided by Transportation Network Companies) A service that arranges one-time shared rides on very short notice. This type of carpooling generally makes use of three recent technological advances: ●GPS navigation devices to determine a driver's route and arrange the shared ride ●Smartphones for a traveller to request a ride from wherever they happen to be ●Social networks to establish trust and accountability between drivers and passengers These elements are coordinated through a network service, which can instantaneously handle the driver payments and match rides using an optimization algorithm. Western Europe's tallest building, the Shard, (310m) has just 48 car parking spaces taking up the room usually needed for just eight cars.

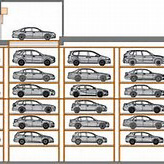

Served by a valet, a driver parks in a space and gets out of the car, which then disappears into the ground. It is then parked automatically into a store and can be called when needed.

References:

[1] Where is Uber Currently Available?". www.uber.com. Retrieved March 26, 2015. [2] "Uberification of the US Service Economy". Schlaf. Retrieved January 5, 2014. [3] Parking, People, and Cities Michael Manville and Donald Shoup. [4] Graph based on data from Vukan R. Vuchic, Transportation for Livable Cities, p. 76. 1999. ISBN 0-88285-161-6 |

Services |