|

The Land : Public or Private - Who Cares?

22/12/2017

barrySays

The idea that land and its resources should be owned or held by individuals, families or companies is a relatively modern idea. Land was traditionally seen the world over as a common asset for use by everyone. However, as populations have increased, the grab for land and its control has become a primary generator of wealth. Private land ownership, coupled with its inheritance over generations, has exacerbated inequality. Once again, the global wealth divide has reached staggering proportions and inevitably social stability is threatened, meaning changing land ownership and management solutions are inevitable. THE COMMON OWNERSHIP

The idea of divine rights of land ownership, ‘god given’ to a human representative on earth, became all-pervasive following the invasion of Britain by France in 1066, having been first introduced by the Romans for their deified Emperors, from whom all land in the empire was held. By the time of the expansion of the British empire in the 19th Century, this version of the feudal system was imposed on about a quarter of the world.

Prior to the Communist Party's takeover, landowners hired peasant tenant farmers to work the land, as in a feudalistic system. After the civil war, land belonging to landlords or wealthier peasants was redistributed among poorer peasants, and under the Five-Year Plan, farmers were encouraged to organize large, socialised collectives to improve efficiency. (Image: laurenream.github.io. )

THE GRAB FOR LAND

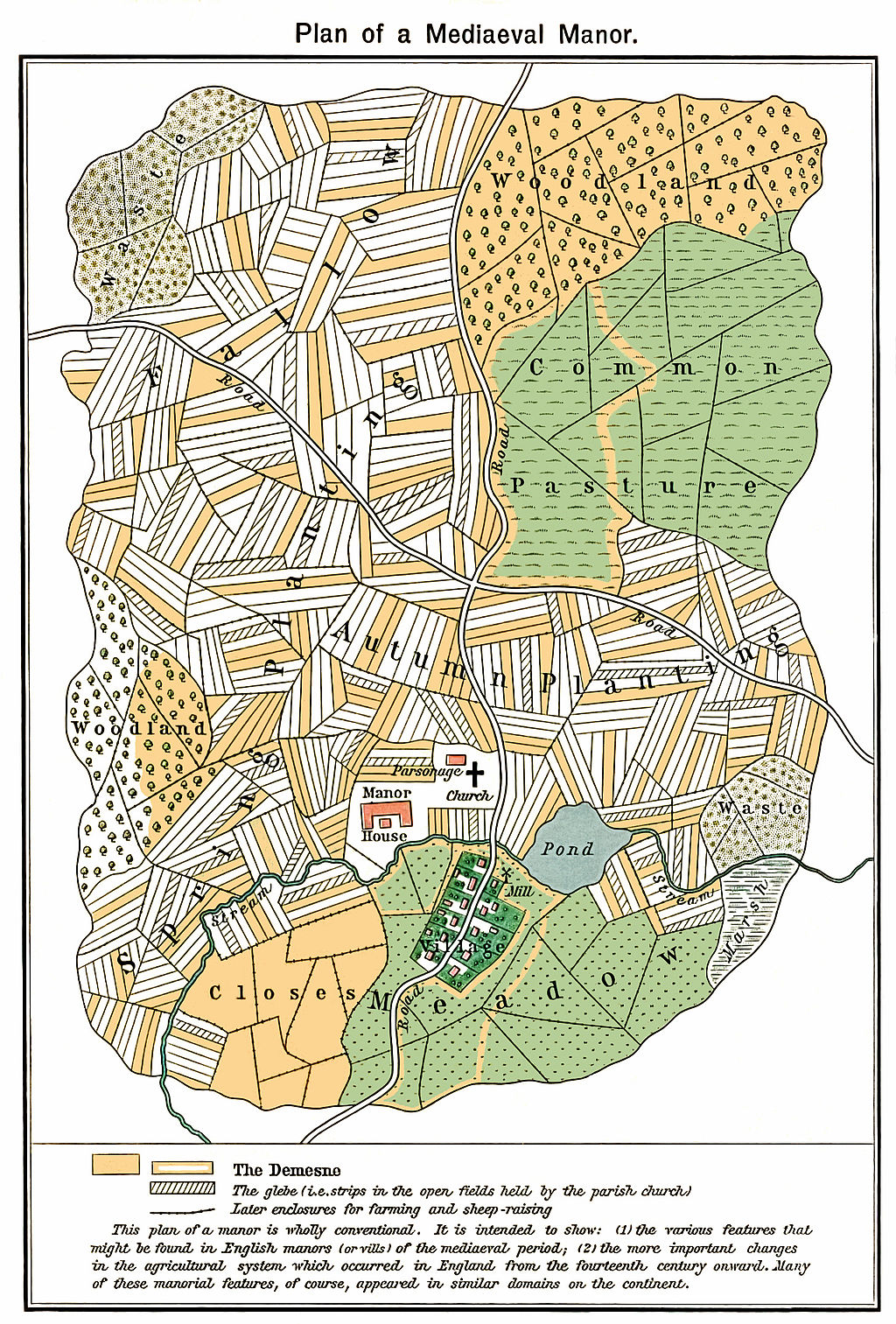

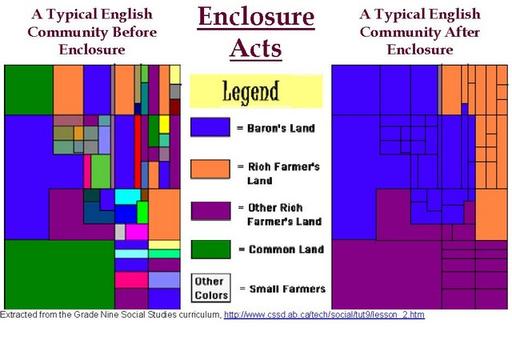

Communal farming of open land, which dominated the central counties of England throughout the late medieval and into the modern period, is a classic common property system that can still be seen in many parts of the world because it affords large economies of scale to small farmers. As England progressed to modernity however, communal land use came under attack from the wealthy gentry who wanted to privatise its use and used their power and influence to benefit directly.

English history is a succession of rural uprisings and depopulated villages as the peasantry responded with a series of ill-fated revolts, starting with the 1381 Peasants' Revolt and Jack Cade's rebellion of 1450 where land rights were a prominent demand.[3] By the time of Kett's rebellion of 1549 enclosure was the main issue, as it was in the Captain Pouch revolts of 1604-1607.[4] Between 1760 and 1870, about 7 million acres (about one sixth the area of England) were changed, by some 4,000 acts of parliament, from common land to enclosed land, whereby the beneficiaries were frequently the very members of parliament enacting the legislation.[5] The people had not only customary and legal access to lands snatched away from them but the very basis of their livelihoods. The census of 1873 exposed the inequity of land ownership in Victorian Britain - that all land in the UK was then "owned" by just 4.5 per cent of the population. Most land was by then the property of a very small network of aristocratic families, most of which had dual links to the House of Commons and the Lords. Those who owned everything also had political control of everything. Britain set out, more or less deliberately, to become a highly urbanised economy with a large urban proletariat dispossessed from the countryside. It wascharacterised by highly concentrated landownership including farms far larger than any other country in Europe. Industrialisation and urbanisation tripled the population of cities in just 50 years between 1851 and 1901. At the same time the rural population declined by 1.4 million people whilst the total population of England and Wales' rose by 14.5 million.[6] By 1935 the rural population was spread remarkably thin, with one worker for every 12 hectares in the UK compared with one for every 3.4 hectares across Europe.[7] Enclosure of the commons and privatisation of land use, more advanced in the UK than anywhere else in Europe, played a key role in Britain's urbanisation at the time, and was consciously seen as a main driver of transformation. The aristocratic families and traditional landed gentry, having withheld the longstanding common land usage rights from the peasantry, were able to sell long leases given by the Crown for building development. Today just 36,000 people (0.06% of the population) have the rights to more than half of the rural land in England and Wales. [8]

As China rapidly industrialises and urbanises it has also had to develop ways to marketize land use and raise money. It has similarly addressed this by selling long-term leases on urban land, known as land-use rights (LURs) for an up-front payment whereby the land will theoretically revert to the state at the end of the term. These rights are currently set at 70 years for residential land and 40 years for commercial property that are tradeable, subject to basic planning restrictions, and compensable if expropriated by the state. However they have been issued without clarity on what will happen at the end of the leases. Last year, following the National People’s Congress, Premier Li Keqiang suggested Beijing will permit perpetual free renewals, and that the government is in the process of drafting the relevant legislation. Perpetual free renewals could mean that people who paid for a 70-year use right now find themselves with what could be otherwise simply called ‘private land ownership’.

DISAPPEARING PUBLIC SPACES

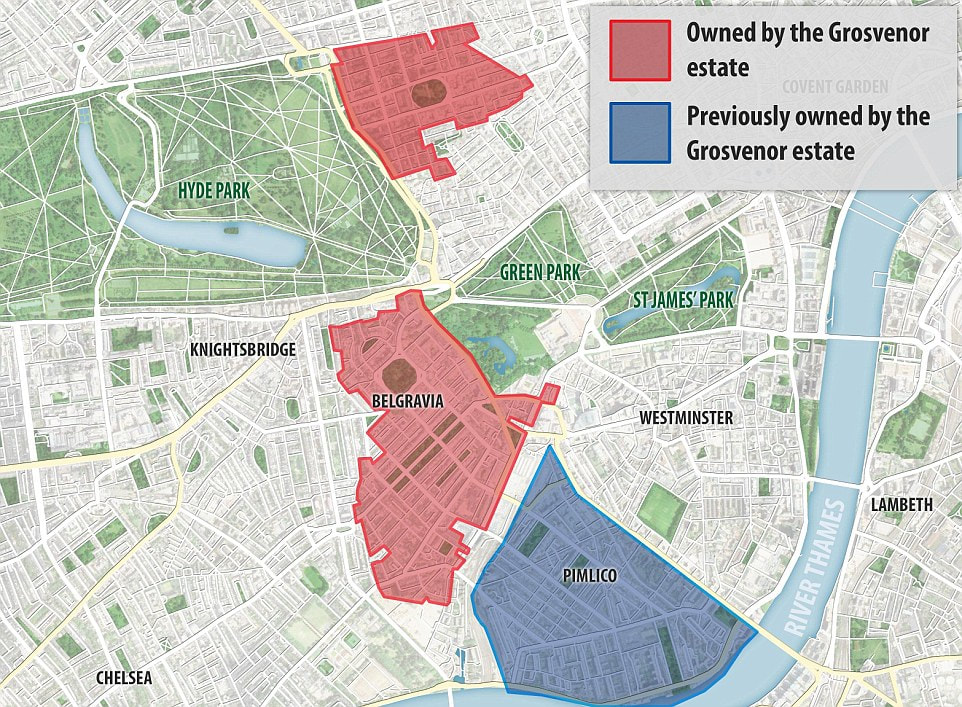

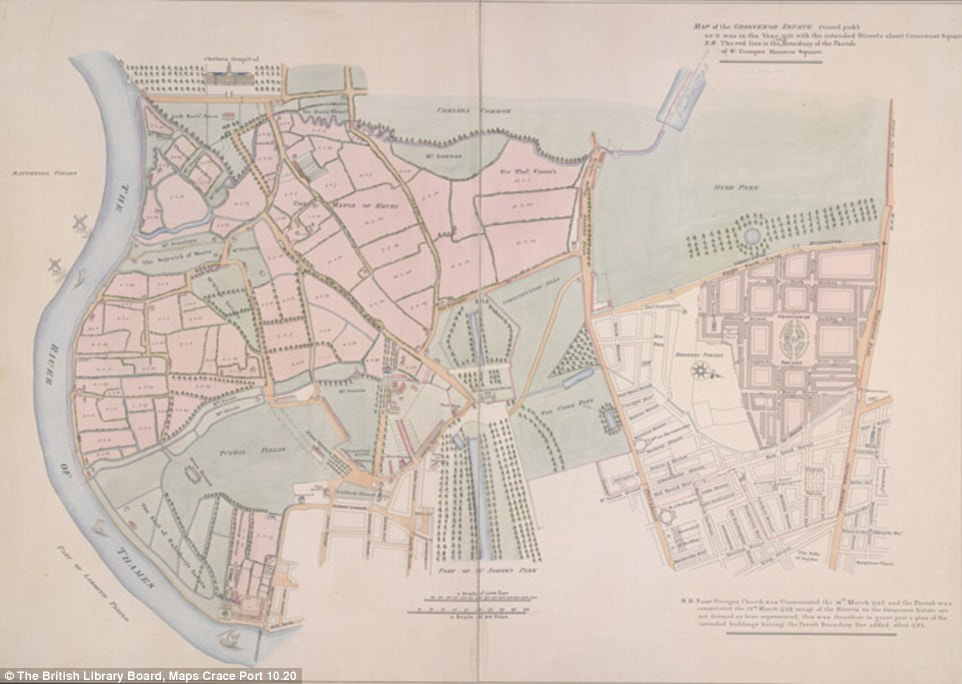

One percent of the world’s population now owns over 50% of the world’s wealth.[9] In London, large swathes of the capital are owned by six “great estates” such as the Grosvenor Estate, dating back to 1677. England’s old aristocratic fiefdoms have now rebranded themselves as large corporate enterprises and are now in competition with global players to gain further control of public space in cities.

COMMUNITY MANAGED CITY SPACE

The adoption of gated residential communities in China’s development boom has been a standard model. The system has its roots in the country’s ancient, medieval cities, but the idea really took off with the advent of the centrally-planned work units of the communist economic system in the 1950s. These compounds are generally open to pedestrian access, but many forbid cars of non-residents whilst others even prevent passers-by from entering.

In 1677 the London heiress Mary Davies married Sir Thomas Grosvenor, bringing with her the ownership of 500 acres of swampland, pasture and orchard, but more importantly it was unencumbered from common use by a public then disenfranchised from their historical land use rights. This today is some of the most expensive real estate on the planet where more than half of that land in London’s Mayfair and Belgravia is still ‘owned’ by Mary and Sir Thomas’s descendants as Grosvenor Estate.

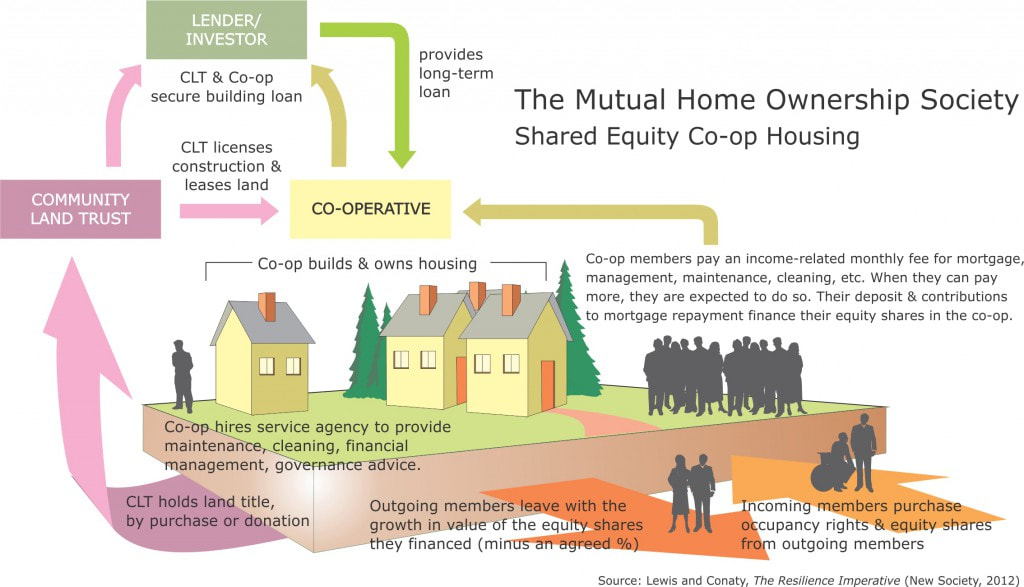

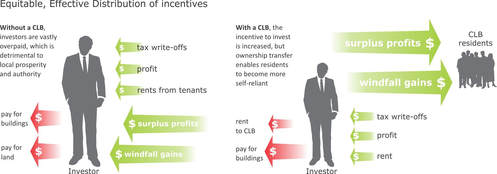

CLBs could help democratise economies. Land speculation would give way to a positive and structured incentive to invest in transparently productive businesses, to which the cost of urban land would prove less of a hurdle. By capturing rising property values and surpluses, CLBs would pool investment assets which could be applied to local transition challenges. (Image: Don McNair)

Barry Wilson is a Landscape Architect, urbanist and university lecturer. His practice, Barry Wilson Project Initiatives, has been tackling urbanisation issues in Hong Kong and China for over 20 years. (www.initiatives.com.hk).

2017/11/10

Hong Kong to Benefit by Revitalising Water Bodies 2017/10/17 Return Healthy Streets to the People 2017/09/20 Has Housing Reached a New Tipping Point? 2017/07/18 Superficial Beauty Conquering Urban Substance |

Reference:

[1] 'A Short History of Enclosure in Britain' - The Land Magazine, Issue 7, Summer 2009 [2] Has China Restored Private Land Ownership? The Implications of Beijing's New Policy, Foreign Affairs Magazine, May 16, 2017 - Donald Clarke. [3] Jesse Collings, Land Reform,: Occupying Ownership, Peasant Proprietary and Rural Education, Longmans Green and Co, p 120; and on Cade p138. [4] WE Tate, The English Village Community and the Enclosure Movements, Gollancz,1967, pp122-125;W H R Curteis, op cit 10, p132. [5] G Slater, "Historical Outline of Land Ownership in England", in The Land , The Report of the Land Enquiry Committee, Hodder and Stoughton, 1913. [6] Institut National D'Etudes Demographiques, Total Population (Urban and Rural) of metropolitan France and Population Density — censuses 1846 to 2004, INED website; UK figures: from Lawson 1967, cited at http://web.ukonline.co.uk/thursday.handleigh/demography/population-size/...population nearly tripled. [7] Doreen Warriner, Economics of Peasant Farming, Oxford, 1939, p3. [8] Who really owns Britain? Country Life November 16, 2010 [9] Credit Suisse, the 2017 Global Wealth Report [10] New Oxford American Dictionary. |

Services |