|

Hong Kong to Benefit by Revitalising Water Bodies

10/11/2017

barrysays

The following article initially appeared in the Construction+ Magazine.

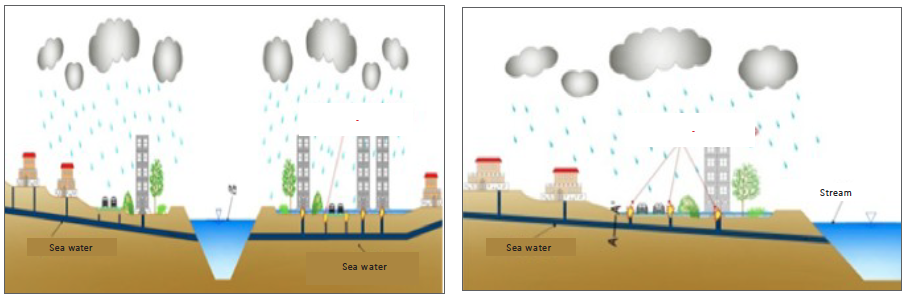

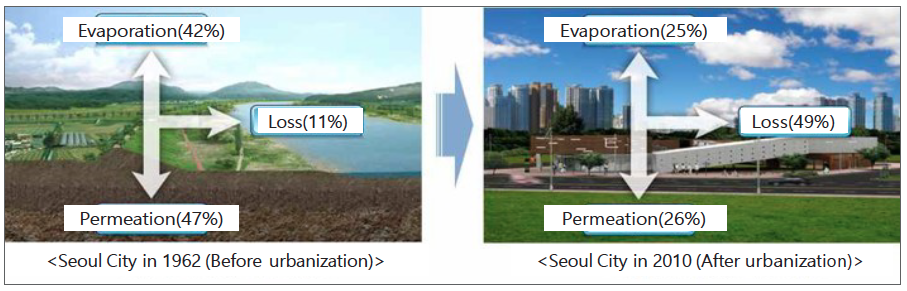

Increasingly intense and frequent torrential downpours are becoming the norm around the world, and the time for denial of climate change is over. Adapting our cities to be more resilient will be the theme of the next decade, yet many cities seem to be quite ill-prepared, having both developed in high risk areas as well as implemented storm water drainage systems based on historical statistics. Business-as-usual water management approaches remain prevalent in the form of channels, underground pipes, dams, levees, gates and tunnels, resulting in flooded streets, submerged metro stations, not to mention the massive loss of natural environmental systems. Things have got to change.

Revitalisation of Tsui Ping River

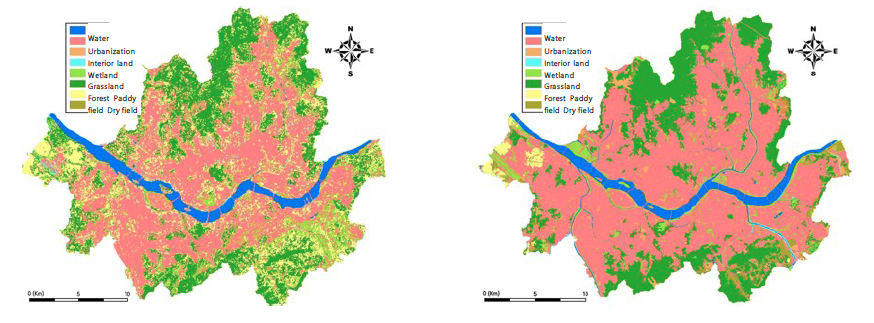

The Seoul Experience

Historical Approaches

Water Management Integrated with Urban Design

Barry Wilson is a Landscape Architect, urbanist and university lecturer. His practice, Barry Wilson Project Initiatives, has been tackling urbanisation issues in Hong Kong and China for over 20 years. (www.initiatives.com.hk).

2017/10/17

Return Healthy Streets to the People 2017/09/20 Has Housing Reached a New Tipping Point? 2017/07/18 Superficial Beauty Conquering Urban Substance 2017/06/14 10 Simple Ways to Futureproof Our Cities |

Construction+ is a bimonthly magazine that seeks to present extensive, in-depth B2B insights and updates from and for the building and design industry.

|

Services |