|

MINDSET THE KEY TO CHANGING CITIES

03/12/2018

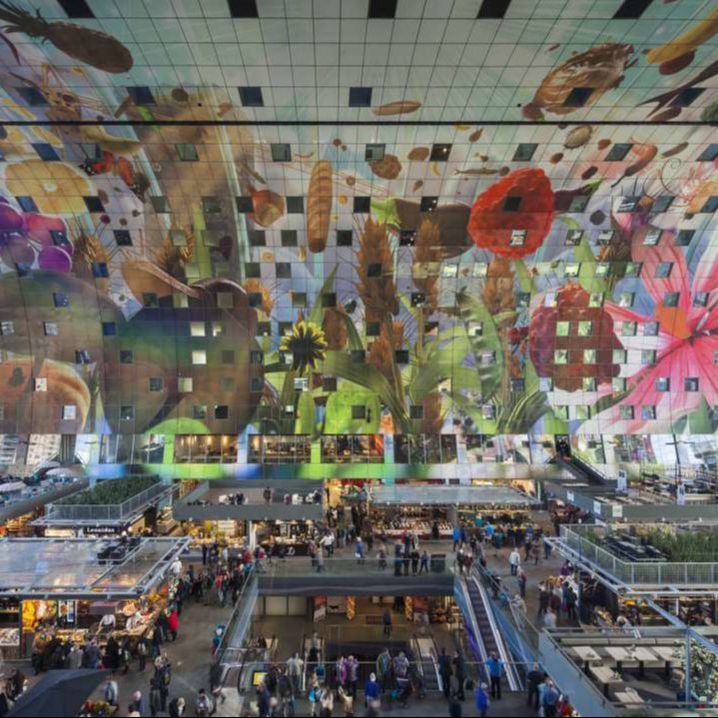

Difficulties watching video? Please watch it on Youtube or Tencent video barryshares

Before this year's Conference of the Hong Kong Institute of Urban Design - “Actions for Active Ageing–Urban Design for All,” I wanted to take some quality time in advance to personally greet the speakers and understand their particular passions and knowledge areas, as well as to brief them on the objectives of the Conference. Whilst several speakers were relatively new to Hong Kong, Marta Pozo Gil, Asia Director of design superstars MVRDV, was a regular local visitor, being based in Shanghai. We meet for the first time. The first thing that strikes you about Marta is that she is tall, really tall. And confident; her bright, shining ‘dutch-orange’ shirt exudes confidence. But then confidence is a basic Dutch attribute and Marta has been absorbing that confidence in working with a company like MVRDV for more than 10 years. Funnily however, Marta is in fact Spanish, from the town of Valencia, working first in Berlin and then Rotterdam before now turning ‘Chinese’. We want to talk about change. Change in the cities and change in mindset.

PEOPLE AND STREETS

Dutch urban planners smartly diverged from the car-centric road-building policies being pursued throughout the urbanising West. In many cities, cycle paths are completely segregated from motorised traffic. Sometimes, where space is scant and both must share, there are street signs showing an image of a cyclist with a car behind accompanied by the words 'Bike Street: Cars are guests'. At junctions too, it is those using pedal power who have priority, where cars (almost always) wait patiently for you to pass, the idea being that "the bike is right".

The development of ‘Woonerf’ (living yard), abundantly applied throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s and still prevalent, legally and officially prioritises the living functions of the street - walking, talking, playing, over and above the traffic function, using the full width of the street space to walk and play. Traffic in a ‘woonerf’ is restricted to "walking pace", at 15 km/h and parking is also restricted. Streets were adapted further with the work of Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman, who pioneered the ‘Shared Space’ method, an urban design approach that minimizes the segregation between modes of road user. This is done by removing features such as kerbs, road surface markings, traffic signs, and traffic lights, making it unclear who has priority, drivers will reduce their speed, in turn reducing the dominance of vehicles, reducing road casualty rates, and improving safety for other road users. THE PROCESS

|

|

Marta explains how doing things differently implies extended effort, research and detailed work to demonstrate to the client and government than an ‘innovative plan’ can work. Nevertheless progress only comes by challenging the status quo. In China there is a strong willingness to try new approaches rather than the resistance to change that is typical of western culture. However, “where policies, social behaviour and support systems are different, just copying or transferring overseas solutions can’t work” says Marta. “There need to be local solutions to local problems, but bringing in thinkers from different backgrounds is crucial to generate new perspectives and to view things through a different lens. Only then, can change truly come. Again, it’s the process that’s important.”

|

Ah, the process, but what is the key to this process exactly? “There needs to be an understanding from all parties that the project will be adapted regardless. There are always local ingredients of lifestyle, needs, and aesthetics, that are different and even if you try to strictly follow an overseas example there are codes, laws, systems and guidelines that will adjust the project and localise it. The process shapes the outcome.

A project must address the identified needs of the people who will use it. It’s essential therefore to engage all the stakeholders early in a project, including the urban neighbourhood, and not just carry out physical mapping alone. Success can’t be judged on the quality of the materials used, the way it looks or compliance with technical guidelines or ratings. The programs delivered must be ‘relevant’, not just be the guesses or instincts of the designer, government or officials; the project must function primarily for the end users. In The Netherlands it’s the ‘community’ that are primarily the neighbourhood managers and not the ‘government’, which fundamentally alters the end use objectives of a project. “We must also be guided by density however, where there is more concentration, outcomes resonate more.”

CHANGE IS COMING

|

Marta is ‘fascinated’ by many things during our discussion but ‘change’ is the main one. “It’s fascinating to see the multiplicity of things that are happening all at the same time, together, in the same place.” “Technology and energy supply will soon change the whole fabric of the city and the way people are going to live. For instance, last century, cities have been designed around the car. As mobility and urban infrastructure develops, there will be massive transitions coming in how we experience the city. It is already happening that larger areas of major cities are being given back to the people and cars are banned. At the same time new ideas are under test: underground hypersonic transportation; urban air transportation; and new ridesharing apps. We are moving forward at high speed and change is all around us.”

“The built environment has a huge influence on how people act out their daily lives, more-so even than the influence of other people,” thinks Marta. One important technology that will facilitate and accelerate change in our cities is big data analytics. With the ability to collect, organise and analyse large amounts of data, we will be able to come up with an accurate understanding on how people uses the city and how they would like to use it, and therefore we can think of better solutions for our communities, at individual and collective level. Nevertheless, big data comes with big challenges in order to create positive changes. “In any change there will always be people who complain, because it requires people to stop doing things that are familiar and start doing things that are new. People need time to adjust. But humans are incredibly adaptable and very soon they will have forgotten how things were before; sometimes just very simple changes can make a huge difference for the better.”

|

The discussion leads us to consider how China’s development mode is not linear, as in the west, but far more “iterative” or circular. Every project is a pilot project, a first phase, to be improved upon by being a test bed for real time learning. There is no time to plan too carefully and in too much detail, the pace of change is too fast; spend a long thinking and the baseline will have changed, the market will have already moved on. “Speed is good,” thinks Marta. “It promotes change, and change is generally a good thing. What’s more, good changes promote further better changes. However, speed definitely affects people, it puts them under pressure, makes them nervous and less reliable. The pressure of speed can lead to chaos and this to a breakdown in communication. Its then that the quality of expectations aren’t delivered. Problems don’t come from speed, problems come from poor communication.” So high speed can lead to fast learning, but also poor communication, and this is what we have in China.

INCLUSIVITY OR MARGINALISATION?

|

Marta is also ‘devoted’ to complexity. “We need to move to more social living, we are social animals but at the moment everything is about profit and measured by performance. We have to put social issues to the front, and then balance them with those of economics.” She has just read professor Saskia Sassen’s ‘Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy’ and voices her concerns raised in the book of globally soaring income inequality, displaced populations and accelerating environmental destruction. The book presents how these can be understood as a type of ‘expulsion’ of people from professional livelihood, from living space, even from the very data of existence. “People not contributing to economic data no longer seem to really exist and are excluded from planning and progress. People are either born lucky or not lucky.”

Coming back to the focus of the Conference therefore it seems that the elderly are a group that have all too often been included in the non-productive demographic, leading them to be “expulsed”. However, nobody can escape the age trap; nobody gets lucky in an ageing population, not even the wealthy. Everyone can relate to the elderly in their family, and can understand that they themselves will be in the same position one day. We therefore finish in agreeing that the importance of building inclusive city spaces that don’t marginalize the elderly will be increasingly normalised. “In that sense I’m positive” smiles Pozo.

|

2018/08/07

Managing Trees in the Urban Environment

2017/10/31

Housing is not a Speculative Commodity

2017/08/29

Take an Alternative Hong Kong Architecture Tour #3

2017/06/27

Towards A New Urban Solution

Managing Trees in the Urban Environment

2017/10/31

Housing is not a Speculative Commodity

2017/08/29

Take an Alternative Hong Kong Architecture Tour #3

2017/06/27

Towards A New Urban Solution

Marta Pozo Gil is an Architect, licensed BREEAM assessor and LEED green Associate. She has worked at MVRDV since 2007.

In 2014 Marta was relocated to Shanghai to head the firm’s Asian office to expand the MVRDV profile in the Asian market as well as to oversee Asian projects.

In addition to her role as Director of MVRDV Asia, Marta leads the Sustainability department for MVRDV

In 2014 Marta was relocated to Shanghai to head the firm’s Asian office to expand the MVRDV profile in the Asian market as well as to oversee Asian projects.

In addition to her role as Director of MVRDV Asia, Marta leads the Sustainability department for MVRDV